At the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan you can find three to-scale models of sculptures created as prototypes for large public monuments. The most well-known is the model for the Statue of Liberty. The second is the famous sculpture by Saint-Gaudens of Abraham Lincoln that was completed for the city of Chicago. The third is one that was not selected, considered but not chosen. The unchosen model was called "Freedman" by Ward.

All three statues are very distinctive. One is a complete allegory (Lady Liberty), the other is very historic (Lincoln standing by a chair), and the third is a blend of the two (a former slave who is an anonymous symbol for four million people). One is a colossus, and the other two were meant for pedestals in parks. Yet, what binds them all together is the inability to speak to or mention the emancipation of the slaves during the Civil War. It was as if it could not be spoken; certainly not cast in bronze and put in the center of a town. The Civil War was over; the union prevailed; the southern states were now free to preserve their culture. Best to leave it at that. Each of these statues struggle with this demand for silence.

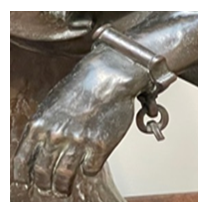

Since I learned about the shackles at the feet of Lady Liberty, I have been trying to find a moment to revisit the statue. I never knew she had broken shackles peeking from beneath her dress; I didn't know there were shackles at all. Yet, once I discovered that the early version of Liberty had a set of shackles in her hand, I wanted see this. Ultimately, the shackles were replaced by a book with the date etched upon it.

While I still plan on a return to Governor's Island, the model at the Met has sated my curiosity. The shackles are there, but not obvious; the message of liberation remains, but it is quietly spoken, as if it is immodest to even notice, let alone mention. The shackles could not be the point of the statue. This was deemed too painful, too provocative.

Saint-Gaudens statue bares a similar modesty. Lincoln is looking forward, but down; he is standing, but he is still contemplating. Behind him is an empty chair suggesting the past, his infamous posture of repose has been left behind. Perhaps he is walking to eternity (a martyr), perhaps he is standing because the war now is over. He seems resolute and his gaze is clear, but there are no laurel wreaths, no winged victory lifting him, no symbols at all. He doesn't hold a speech or a pen; he clutches his lapel and his other hand is unseen. He is free, but still held captive by his thoughts.

This statue of Lincoln, and so many more, were called for after his assassination. Communities in the Northern states wanted to remember Lincoln, to memorialize his life and death. The statues of Lincoln were a way for us to be thankful for his sacrifice, he "preserved the union" at great cost.

Ward's statue of "Freedman" is unique to the three in that it was never built. Ward wasn't the only sculptor who tried to convey the emancipation in stone and bronze, but his model was too early, too controversial. It would be almost fifty years later (1922) until such a monument could be constructed. Thomas Ball's "Emancipation Memorial" was dedicated in a then quiet corner of Washington D.C.

Elements of Ward's design could be seen in the statue that came to be. The former slave is crouched, but rising, clad, but not fully. His shackles are broken, but he is not alone. Standing above him is Lincoln with a hand outstretched as if to offer a blessing. Lincoln is giving the former slave his liberty. In Ward's design, there is only the former slave, no clear indication how the chains were broken, no aid in his rising. He is looking up, ahead, even if it is behind.

What I found so compelling in the three statues was the difficulty to speak of the legacy of slavery. Any attempt to bring it up was met with resistance. It was as if the "sins" Lincoln spoke of were paid for by those who died during the Civil War and now we are moving on. Slavery and emancipation were done, paid for. Leave it alone. Lady Liberty has no shackles; Lincoln is not a "liberator" he is a sacrifice; and any statue of "Freedman" should be tucked into quiet corners of a park.

As my research and study of monuments and memorials and museums progresses, I am not sure we are best served by quiet corners. Sometimes what is silenced is what is needed to be said the most.

From 1885-1925 there were more than 4000 monuments and memorials erected in public squares and parks (1,500 in the "Northern" states and 2,500 in the South) to remember the Civil War veterans. Each speaks of a great struggle, a great sacrifice to "preserve."

It was a war to preserve the union or preserve state sovereignty. This was not an obscure message or the opinion of a few; this is town squares, public parks. Yet with this proclaimed message came the demand for what would be unspoken; this was not about liberating 4 million people from the bondage of slavery.

I am not sure what to do with the silence. It certainly persists. We are held by a persistent shackle.